Toxic polarization is killing us. A new worldview can save us

Understanding our political predicament through a 'worldview lens'

On the political left1 we tend to think we’re on the right side of history: we want to create a more inclusive economy and society while addressing urgent environmental problems like climate change. If put into practice, we believe, our views will surely lead to a better world for all. Yet, the public is not compelled. Why is this so?

Why has right-wing populism surged across the planet, with populist parties over the last two decades steadily gaining power, culminating in the re-election of Trump?

Why has the 2024 election year, with countries with more than half of the world’s population going to the polls, resulted in such a harsh repudiation of the left?2

Why has the dire state of our planet, as well as the rampant inequality in societies across the globe, not translated into support for the political parties wanting to address those issues?

Why are we (still) enmeshed in a destructive, decades-old culture war that sabotages our capacity to forge solutions for the daunting problems humanity faces?

And what is the the opportunity for renewal — if not transformation — hidden in this crisis that the left is facing?

In this essay I argue we cannot adequately answer these questions without adopting a worldview lens. Such a lens enables us to contemplate the deeper origins of our political battles, so we can grapple with the ideas underneath the different positions. It also helps us make sense of the rapidly evolving shifts in our political landscape, ‘zooming out’ and recognizing overarching patterns and trends. Finally, a worldview lens supports us to examine if our current worldview still serves us — or fails to do so — thus creating a foundation to re-think, and where needed, evolve it.

Such deliberate worldview-examination is particularly important to the left. With far-right parties in power, it needs to present a real alternative — both to what the right offers, as well as to its past offering, which has failed to convince and inspire. This will become even more urgent when the public wakes up to the reality (or tyranny) of what it has voted for. However, we can only develop a viable alternative if we are to critically self-investigate. Adopting a worldview lens offers us a potent opportunity to do so, helping us explore issues from diverse perspectives, cultivating a more rounded vision — one that’s truly inclusive, rather than exclusive and elitist.

I’ll offer a framework attempting to explain major political dynamics of our time (e.g., populism, worldview polarization), while honing in on the main (i.e. postmodern) worldview that has invigorated the left, particularly in the West3, for the past decades. I’ll illuminate how some of the left’s signature positions (e.g., its globalist-, identity-, and gender-politics) are substantively contradictory and both an expression of current polarization-dynamics while also fuelling them — thus unwillingly inviting for far-right populism. I conclude that a new worldview is needed that can enable the left to skilfully ‘manoeuvre’ us out of the culture wars while delivering on its greater promise of addressing humanity’s urgent planetary challenges.

Adopting a worldview lens

Historians, sociologists, and philosophers have often looked at society with the aim of detecting the larger, overarching patterns in how humans make sense of the world, thereby shaping their behaviors and socio-economic organization. These worldviews are the lenses through which people see and filter reality writ large, informing individual choices and group identities, lifestyles and political preferences.

Max Weber, a founding father of modern social science, was an early voice pointing out how humans’ conceptions of the cosmic universe shaped the socio-economic organization of their societies — as he did in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, one of the great influential books of all time. While Weber held that cultural and religious conceptions profoundly shaped socio-economic organization, he did not conceive of worldview as offering a total explanation, but rather as a crucially important variable to be considered.4

Rather than as a collection of discrete beliefs, Weber argued that a worldview functions as an overarching system of meaning-making — as a big, somewhat coherent ‘story’ that answers universal, existential life questions for us. Questions like: What is reality? How can we come to valid knowledge? What kind of creatures are we? What does it mean to live a good life? And how should we organize society?

As our worldviews answer these vital questions for us, they assert what is true, valuable, moral, and possible, thus instilling a sense of who we are, where we come from, and where we’re going. In this way, they provide us with the sense that life is meaningful, manageable, and stable — and Weber considered this meaning-making satisfaction to be their central function. Though a worldview is in practice often unconscious and habitual, it does come to expression in myriad practical ways, including in our cultural movements and political struggles. As the cultural historian Richard Tarnas put it succinctly: “World views create worlds”.5

Importantly, Weber conceived of different categories of worldviews as ‘ideal-types’, that is, as rationally constructed, somewhat logical frameworks of meaning that do not quite show up in these ‘pure’ or ‘ideal’ ways in the messiness of social reality, yet offer a potent heuristic to examine that very complex reality. Instead of getting lost in the many details and nuances, these ideal-types help us recognize overarching patterns and ‘see the forest through the trees’.

Though worldviews are immaterial — they live in our minds and hearts, our language and stories — I treat them as significant psychological and cultural forces that inform and mobilize people, including the political and economic systems they (re-)create. As they tend to emerge in response to the problems of a certain time, each worldview brings forth new insights, solutions, and qualities, as well as more problematic aspects. However, pushed by contemporary polarization-dynamics, worldviews may over time grow into caricatures, manifesting in increasingly extreme and problematic ways. And while humans often hold a dominant worldview, we’re all shaped by the Zeitgeist, the ‘ecosystem of worldviews’ that our cultural landscape consists of.

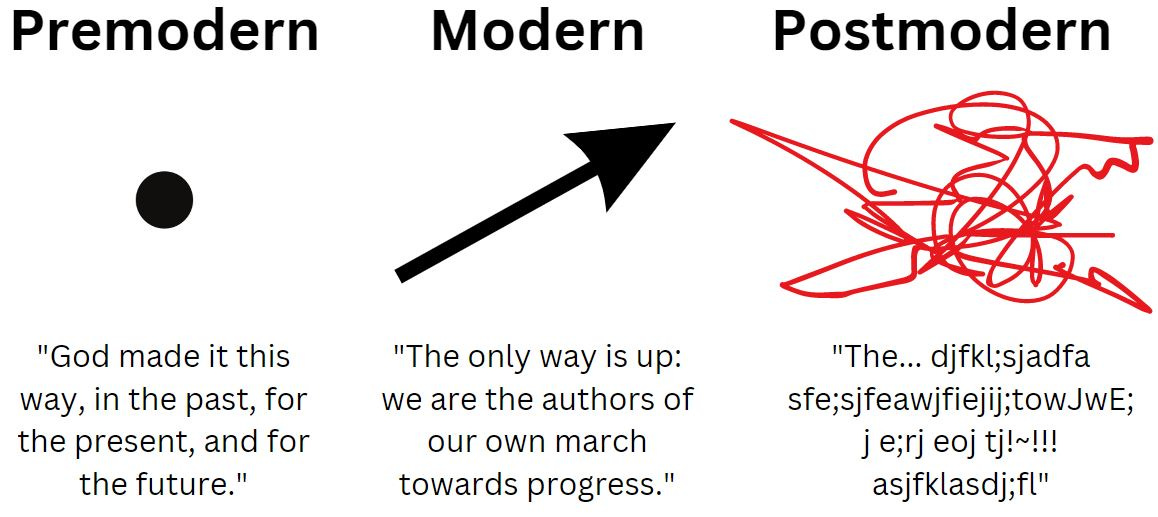

Three worldviews dominate our current cultural landscape

In the West, we’ve seen massive shifts in our worldviews over time. Sociologists and philosophers have described a move from more traditional, frequently religion-based worldviews that emphasize social-traditional values and conformity to family and community, to more modern worldviews, in which science, rationality, and technology have become central, empowering the individual and emphasizing a materialist, hedonist value set. This change is often understood to have started with the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, and coincides with the transformation from agricultural to industrial societies. Generally speaking, it resulted in a naturalist, materialist understanding of reality — sometimes called the ‘Clockwork Universe’.

Since the 1960s, cultural elites within academia and the arts started forging a new postmodern worldview, which coincided with the emergence of the postindustrial (or information) society. This worldview was grounded in criticism of Modernity’s ideas of progress, its objectivist science, and the ecological destructiveness and social injustices of its capitalist economic model. Instead, it emphasized relativism and egalitarianism, pluralism and constructivism, as well as ways of knowing beyond the rational — like the subjective and emotional, the moral and artistic. Its attempt to redress the problems of Modernity came to expression in the rise of progressive movements for causes such as the environment and civil rights, peace and nuclear disarmament, and the emancipation of minorities, women, and gays.

While postmodernism may be understood as a (perhaps obscure) academic philosophy with roots in French critical theory, its ideas rapidly spread to other parts of the academy as well as to activism, bureaucracies, NGOs, and education. While shaping the public’s views, postmodernism also appears to reflect a value shift in the public at large. That is, as economic conditions had greatly improved the material quality of people’s daily lives, particularly since the 1950s-60s, thus nurturing a sense of existential security, orientations gradually shifted from survival to self-expression values, and from material to postmaterial values — changing worldviews and political attitudes in a more progressive, cosmopolitan direction. This profound cultural transformation has been documented by a substantial body of survey-based research.

Though some may argue that postmodern thought and progressive culture are distinct — yet overlapping — phenomena, I understand them as different expressions of the postmodern worldview.6 Practically, postmodern thought has provided intellectual fuel for progressive movements, giving them the concepts to deconstruct ‘dominant discourses’ (e.g., patriarchy, colonialism, white supremacy), elevate marginalized voices, and question the idea of neutrality. And while postmodernism as philosophy may be out of fashion in many academic circles, its influence in the cultural DNA of much of today’s progressive activism is arguably alive and well. This comes to expression — as we will see — in ideas like identity as constructed, power as everywhere, and language as a prime site of struggle in the aim for change.

These three broad, widely-recognized, ideal-typical worldviews — traditional, modern, and postmodern ones7 — have the potential to powerfully illuminate the political dynamics in our world. It is these worldviews I’ll therefore draw on here.

Explaining populism: Economic insecurity and cultural backlash

To explain the phenomenon of populism, competing accounts are often invoked, pointing to either economic insecurity or cultural backlash as central cause.8

Populism’s key assumption is that the interests of ordinary people are fundamentally opposed to those of elites, with populists claiming they — and they alone — represent the ‘pure people’ (while the ‘corrupt elite’ represents ‘special interests’). Political scientist Cas Mudde describes populism, particularly in the context of post-war Europe, as “an illiberal democratic response to democratic illiberalism”, arguing it’s a revolt against the lack of options within a closed political space, which itself is the result of processes that are only nominally democratic.

That is, as both right and left over time came to favor technocratic globalism over nationalist sovereignty and neoliberalism9 over protection of local workers, a remarkable abdication of power to the market, supranational organizations, and technocratic institutions took place. While educated elites generally benefited from these changes, less educated groups did not, and they, by many metrics, saw their circumstances in life degrade. As David Brooks put it in plain language:

… over the last many decades we in the educated class built a system that is rigged. … we passed a series of immigration, trade and education policies that benefit us, and hurt those without our degrees. High-school-educated people die eight years sooner. They have fewer friends. They marry less and divorce more. The education gap between the rich and the poor is now greater than the education gap between whites and Blacks in the age of Jim Crow. … In short, if you build a system in which the same people win every time, the people who have been losing will eventually flip over the table.

Economic and cultural dimensions are thus intertwined, with economics both underpinning and expressing cultural valuations (e.g., pay as sign of social recognition). That’s why economics alone can’t solve the problem, as Brooks argued:

The Biden administration was built on the theory that if you redistribute huge amounts of money to people and places left behind, they will return to the Democratic fold. It didn’t happen because you can’t use money to solve a problem primarily about recognition and respect.

As political philosopher Michael Sandel argued, people felt not only left behind economically, but also culturally. They felt looked down on by the elites; their voices being of no significance. They felt the moral fabric of family, community, and nation unravelling, leaving them hungering for a sense of belonging, pride, and solidarity.

While economic insecurity is thus crucial for understanding populism, the cultural dimension cannot be ignored either. Political scientists Inglehart and Norris speak of a cultural backlash, understanding populism as a counterrevolutionary reaction to the progressive, cosmopolitan values that emerged on a large scale in the past half century, challenging the once-dominant values and customs of Western societies:

Throughout advanced industrial society, massive cultural changes have been occurring that seem shocking to those with traditional values. Moreover, immigration flows, especially from lower-income countries, changed the ethnic makeup of advanced industrial societies. The newcomers speak different languages and have different religions and lifestyles from those of the native population—reinforcing the impression that traditional norms and values are rapidly disappearing.

Immigration is thus perceived to exacerbate these unwelcome value changes, perhaps even becoming their prime symbol.10 Support for populism may therefore be understood as an attempt to protect one’s threatened worldview. That is, people support populist leaders who defend traditional values and nationalist identities, who reject outsiders and uphold traditional gender roles, and who reflect their own mistrust of the establishment — which had largely come to consist of educated progressive elites.

In other words, today’s culture wars reflect an existential battle between different worldviews. Indeed, James Davison Hunter, the first to apply the concept of culture war to American life in a 1991 book, argued that the culture war is not just a class conflict, with different socio-economic groups standing in opposition of one another, but rather a conflict about worldviews — about "allegiances to different formulations and sources of moral authority" and about "how we are to order our lives together.”11

Hunter distinguished between two polarized camps — orthodox versus progressive (or in our language: traditional versus postmodern) — struggling to "define America.” He offered gay rights as telling example: for one a severe assault on the traditional family, itself seen as the cornerstone of society, for the other the ending of unjust systems of oppression. Both groups thus operate from different assumptions, rules of logic, and moral judgment, such that they live in different worlds and speak past each other.

While our culture wars thus involve a battle between traditional and postmodern worldviews, both have over time grown increasingly suspicious of the modern worldview — which not that long ago was the dominant worldview in Western society and the glue holding the post-war liberal world order together.

The modern worldview: Cosmic alienation in a mechanistic universe

The modern worldview has arguably been astoundingly successful. It enabled advances in science and technology that resulted in a dramatic lengthening of life spans and a much more convenient, safe, and comfortable daily life for many, while opening up a wide range of possibilities that were simply unimaginable before. This worldview was also the foundation for the peace and prosperity of the post-war period, with the idea and ideal of the West thriving.

Despite its successes, this worldview was under pressure from its inception. This initially came to expression in the Counter Enlightenment, with the Romantics lamenting the soullessness and artificiality of the urbanizing, industrializing world around them. Instead, they emphasized an intuitive connectedness with nature as vital to humanity’s well-being. A few centuries later, from the 1960s onward, growing awareness of the ecological crisis started to generate large-sale attention for modernity’s problematic relationship with nature, including its faulty assumption of having infinite material growth on a finite planet.

The modern objectivist worldview had made nature into an object to be exploited for our own purposes, rather than a subject that humans exist in meaningful relation with — as it had been understood for most of humanity’s history — thus stripping it of its symbolic, emotional, intrinsic, and spiritual value. Weber famously called this Die Entzauberung der Welt, the ‘disenchantment of the world’, describing the shift to a rationalist, calculating, instrumentalist worldview. As environmental philosophers have argued, this shift is at the root of our global environmental crisis.

This disenchantment also created a kind of cosmic alienation, as humans as conscious, meaning-making subjects were now fundamentally at odds with the objective, unconscious, mechanical universe that modern science had described, creating the dualism and separation so central to this worldview.12 This objectification affected not only our understanding of the world, but also of ourselves as species. Jurgen Habermas therefore characterized Modernity as ‘control over an external nature, and alienation from an internal nature’.

In this worldview, the human being tends to be depicted as a calculating homo economicus or a complex biochemical machine. However, these notions fail to account for our daily human experience — namely that our existence is characterized by a subjective, intimate, interior experience. In the philosophy of mind this is referred to as the ‘hard problem of consciousness’, arguing we cannot explain experiential consciousness through a mechanistic framework. Simply put: machines don’t have experience, so why do we? If reality is merely mechanistic, as the modern worldview assumes, we should not — and yet we obviously do.

In terms of its political philosophy, the modern worldview is associated with liberalism — emphasizing individual freedoms, the rule of law, free markets, and deliberative democracy — as well as with its mutation from the 1980s onward into neoliberalism, emphasizing market deregulation, privatization, and globalization. Though the latter was initiated by Reagan and Thatcher, over time also progressive parties came to embrace these policies, which decreased the focus on economic redistribution and resulted in the left’s gradual loss of its traditional blue-collar constituents.

The resultant gap between workers and the wealthy was further strengthened by the Iraq war, the financial crisis, and the pandemic, which together sowed the seeds for todays’ almost complete disillusionment with the elite. As a Republican adviser put it:

… huge shocks to the nation’s economic system — terrorism and war, the financial crisis and the coronavirus pandemic — had upended many Americans’ lives, but least of all those of the wealthy. The rich did not send their children to war, their banks were bailed out, and they rode out the pandemic working from home.

These crises not only fostered distrust in the soundness of elite expertise but also the conviction that the elite was self-dealing rather than serving the common good.

It also became clear that maximizing material welfare, a core tenet of capitalism, does not necessarily lead to a happy population. In fact, over time the modern way of life became an important cause of stress, loneliness, and ill health, while also being unresponsive to deeper human longings for connection, purpose, and meaning. Our global mental health crisis underscores that, despite our material abundance, we’re not thriving. As George Monbiot pointedly put it: “What greater indictment of a system could there be than an epidemic of mental illness?”

The modern worldview thus left crucial questions unanswered and couldn’t offer a cogent explanation of humans’ experience and world. It also created new problems — many as unintended side-effects from its technologies or associated with its capitalist economy. Just as importantly, it did not result in the health and happiness people desire. These failures empowered the emerging postmodern alternative.

The postmodern worldview: Lost in a polarized, post-truth, purposeless world

Central to postmodernism is the idea that reality is socially and subjectively constructed through paradigms and discourses, rather than having objective, independent existence. Because this worldview challenges Modernity’s notions of truth, objectivity, and rationality, it tends to refuse to commit to (metaphysical) assertions about the nature of reality. (That is, as one questions truth, one can also not claim to have or speak truth.) Instead, it emphasizes ambiguity, uncertainty, irony, relativity, and fluidity. The ontological status of the world is thus unknown, and the idea that the world or the self has an intrinsic nature is rejected.13

This shift, as philosophers contend, started most notably with Immanuel Kant. Not coincidentally, Kant was also the first to coin the notion of Weltanschauung or worldview, in his Critique of Pure Reason in the late eighteenth century. His revolutionary thought shifted the balance from a focus on the objective world ‘out there’, to how humans perceive and construct that world ‘in here’. Known for his distinction between the noumenon (the thing in itself) and the phenomenon (how we perceive it), Kant argued we cannot ultimately know reality, because what we perceive is shaped by the structures (the a priori categories) of our mind — rather than by reality itself, which remains elusive to us.14

This constructivist shift in thinking arguably represents an important advance in our self-understanding. There is great potential for liberation in the realization that how we construct reality — through paradigms and stories, psychological bias and cultural frames — will shape that reality in substantive ways. That is, as we recognize ourselves as active constructors of our world, possibilities open up to do so in ways that lead to a more desirable world. This is sometimes expressed in the popular idea that you can ‘create your own reality’, or ‘write your own story’.

This shift in thinking also offers ample opportunities for political activism, which showed itself in the ascent of new cultural issues, social movements, and political parties. As studies have shown, these reflected an increased tolerance of diverse sexual expression (e.g., same-sex marriage, LGBTQ rights); concern about environmental issues; secular values and norms; openness towards multiculturalism (e.g., foreigners, immigrants, refugees); and support for international cooperation (e.g., humanitarian assistance, multilateral agencies like the UN).15

While the modern worldview, with its story of progress and the liberation of humanity, is characterized by great optimism (or, in its darker expressions, hubris, with humans depicted as the masters of nature or even the universe), the postmodern worldview is noteworthily critical and skeptical — which over time increasingly turned into cynicism. These days, this worldview is utterly disillusioned with the modern story. It sees its notions of science and truth, progress and rationality as ‘narratives’ used by the powerful and privileged to oppress and exploit. It considers its ‘rhetoric’ about democracy and human rights to be merely masking the cruelty of its capitalist civilization. Deconstructing these ‘oppressive narratives’ is therefore of the greatest importance to this worldview.

Through potentially immensely liberating and emancipating, such (de)constructivism can also slip into nihilism and anti-realism. If our human mind does not give us access to reality, as older worldviews had always assumed, then what does ‘reality’ even mean, and what substance or significance does it have, if any?16

Relatedly, the postmodern worldview is deeply egalitarianist and culturally relativist. That is, as it emphasizes the paradigms and perspectives through which we construct our world, it holds that one perspective cannot be ‘better’ than another one, as that would presume some objective viewpoint or universal perspective, which does not exist and cannot be justified within the framework of this worldview.

The results of this shift in thinking are radical. In this postmodern world there are no objective truths, no universal values, no essential qualities, nor intrinsic purposes. Knowledge is constructed, subjective, local, contextual, and relative, and any grand story about life, mind, or the universe is suspect — seen as an attempt at power and dominance. As Lyotard famously phrased it, postmodernism is characterized by an “incredulity towards metanarratives”, a deep skepticism of belief systems that offer broad, cohesive explanations of the world. However, while postmodernism thus represents a new awareness of how our paradigms construct our world, it appears markedly blind to its own worldview — its own postmodern metanarrative.

This disorienting postmodern world — without aspirational meaning frameworks, real value, purpose, or even truth — appears related to what cognitive scientist John Vervaeke refers to as the meaning crisis of our time. While in the modern world human meaning was incongruent with a mechanical cosmos, in the postmodern world it is merely a construction or projection (as the ontological status of the cosmos is ambiguous). The postmodern worldview thereby arguably sabotages humans to fulfil their vital need for meaning — leaving them feeling disconnected, fragmented, insignificant, and purposeless.

The anti-realism at the heart of this worldview17 appears also to be related to the post-truth crisis of our age, as the visionary thinker Ken Wilber argued in his 2017 book. Having deconstructed truth, there’s nothing to guide the human experience, resulting in the narcissism-inducing premise that we might as well do whatever we feel like. That is, when there’s no truth or value, it makes sense to opt for what is most gratifying in the moment or of greatest service to the self (or ego). This coincides with a world in which narcissism runs rampant and people have their own ‘facts’, living in disconnected echo-chambers and polarizing with those with different worldviews.

The war of worldviews: Polarization in the age of ideology

Since Hunter wrote his ‘culture war thesis’ in the nineties, his two major ‘camps’ (of traditional vs postmodern) have only further polarized. And polarization goes hand in hand with radicalization — that is, with the tendency to become more extreme in one’s views. As studies have shown, when like-minded people interact in ‘echo-chambers’, they’re sheltered from influences that challenge their positions, resulting in their opinions becoming more homogeneous, fixated, and extreme. This dynamic has been powerfully exacerbated by social media algorithms in the last two decades.

As both sides radicalize, the distance in positions becomes even harder to bridge. Those who try may be seen as ‘traitors’ by their own side, while being co-opted or exploited by the other. The imagery of war thus appears quite appropriate here. That is, this is a life-or-death struggle — at least psychologically — where both sides fight each other as existential threats, while fuelling each other’s excesses. We can see these self-reinforcing polarization-dynamics in our societal debates, with issues framed as having only two sides, and thus hardly any space for complexity or nuance. You’re either for or against. You’re pro-vax or anti-vax. You’re pro-Israel or pro-Palestine. You’re pro-trans or transphobe. You’re MAGA or Woke. You’re friend or enemy.

Our polarized cultural climate thus exerts a radicalizing pressure on our worldviews, tending to push them in more extreme directions, resulting in them becoming increasingly ideological. Studies have shown that, despite great differences in content — be they left-wing or right-wing, secular or religious ideologies — there is a clearly detectable cognitive structure to ideological thinking, characterized by rigidity in adherence to doctrine and resistance to evidence-based belief-updating, while being favorably oriented toward an in-group and antagonistic to out-groups.

That is, where a worldview contains at least some recognition that it is one of many (possibly valid or insightful) views on the world, an ideology is characterized by the belief that it is the only correct and all-explanatory view. Where a worldview values dialogue and deliberation, aligning with the fundamental principles of liberal democracy, an ideology imposes and dictates, aligning with authoritarian regimes.18

The psychology of worldview-threat

Another aspect to consider here is the psychology of worldview-threat. That is, because humans tend to identify with their worldviews, they may experience themselves as threatened when their worldview is challenged.

Because a worldview fulfils crucial psychological functions, including a sense of meaning and stability, humans tend to employ cognitive biases to maintain their worldviews. Thus, as opening oneself to perspectives or information that challenges one’s worldview may be threatening — or even incur (instant) psychological or mental crisis — humans have in-built tendencies to avoid that. This means that worldviews are inherently vulnerable to becoming ideological. (However, research also suggests that these tendencies may be overcome through a simple practice like mindfulness, which has been shown to reduce worldview-threat and inter-group bias.)

Worldview-threat also has a clear physiological dimension, as the nervous system is designed to increase the chances of survival by automatically resorting to ‘fight or flight’ mechanisms once a threat is detected. This threat-response readies the organism to react instantly, pumping blood and oxygen to the limbs so one can put up a fight or run away. At the same time, it shuts down mechanisms that don’t contribute to in-the-moment survival, including higher cognitive functions like reflection and learning. This threat-response is what people refer to when they say they’re ‘triggered’.

These days, ‘trigger warnings’ and ‘safe spaces’ have become a flashpoint in the culture wars, with one side seeing them as symbols of progressive sensitivity and inclusion, while the other interprets them as symptoms of a coddled (‘snowflake’) culture that avoids discomfort and suppresses free speech. In any case, as studies have shown, openminded exploration becomes practically impossible when this threat-response is activated — as is quite evident in our cultural and intellectual climate.

Also noteworthy in this context is Thomas Kuhn’s historical exploration of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, which famously demonstrated that even supposedly truth-seeking scientists were inclined to resist or suppress anomalies — data that challenged their assumptions — with the aim of trying to protect their scientific ‘paradigm’.19 The tendency to suppress or ignore the inconsistencies that challenge our worldviews is thus universal rather than partisan20 and is best understood as a structural bias of the human mind, also referred to as confirmation bias.

Postmodernism in practice: Progress, but also loss

Understanding this cultural and psychological context is important to appreciate how postmodern thought mutated and diversified over time, from what Pluckrose and Lindsay refer to as ‘original’ to ‘applied’ to ‘reified’ postmodernism21, gradually taking more extremist forms, while fuelling the ‘Social Justice’ movement.

A rallying cry of this movement is inclusion. While inclusion as ideal is laudable, the problem with many postmodern projects is arguably not what they attempt to include, but rather what they exclude in the process.

Take multiculturalism: while representing a significant moral advance, this ‘inclusion’ is often attempted through the sacrifice of boundaries that protect the sovereignty of country, with a cosmopolitan identity replacing (rather than complementing) national identity, which now may be seen as provincialist instead of patriotic. Similarly, the inclusion of minority-identities may be sought through the devaluation of the individual, while the inclusion of people with diverse gender identities is undertaken through overriding sex with gender. I’ll unpack each of these examples below.

Inclusion may be achieved by the dissolution of boundaries and distinctions, or by the integration of them (which preserves distinctions into a larger whole, rather than dissolving them). Postmodernism’s tendency clearly has been to dissolve rather than integrate — blurring boundaries, deconstructing binaries, and diffusing distinctions. Think for example of its blurring of sex and gender, or of the objective and subjective. This impulse to dissolve is both an extension of its sceptical approach to knowledge (i.e., as one challenges the idea of truth, one must also challenge the categories used to describe truth) as well as a reaction to modernity’s dualism (and hierarchical privileging) of subject over object, humanity over nature, and rationality over emotion.

This tendency to rebel against — and override — what came before may be inherent to the pendulum-swing-like process of worldview development. The modern worldview liberated itself from the dogmatism of traditional religiosity and became fiercely secular (or even ‘militantly atheistic’). It left behind its solidarity to social group and cultivated a hyper-individualism. It thus swung to the other extreme. The postmodern worldview, in its pendulum-swing, tried to overcome modernity’s stark dualism and objectivism by positing multiple competing perspectives, laying the foundation for a polarized, post-truth society. Casting aside the modern emphasis on the heroic individual, it became obsessed with group-based victimhood.

While the postmodern impulse to include represents a significant moral advance, if not attained through integration of other (i.e., traditional and modern) valuations, it results in significant losses. And while the left has tended to deny these losses, the right has been unwilling to let them go. The pushback against these losses has often been dismissively interpreted as merely rooted in bigotry, racism, and sexism, thus not acknowledging what’s been sacrificed in progressives’ quest for inclusion — from national sovereignty to the dignity of the individual to the reality of sex.

Globalist politics and the loss of national sovereignty

The maintenance of a secure border to protect the sovereignty of country and national identity is perhaps the central focus of right-wing populists worldwide. Trump’s signature policy proposals of restricting immigration and imposing tariffs both function to shield — to wall off — outsiders from what’s inside: from the country, its economic market, and the livelihoods of its people. Right-wing populists thus react to postmodernists’ dissolution of boundaries and borders by wanting to resurrect them — calling to ‘build a wall’, restrict immigration, and put tariffs on economic markets. They thereby give expression to their sense of who the nation’s system is supposed to serve — insiders rather than outsiders, America first.

Over time, Trump, with his rhetoric and approach — initially out of step with the leading opinion in both political parties as well as with the academic consensus —has, as Schmittz argued, enforced “a change in the way political obligation is understood: It entails a clearer realization that it is permissible, and often essential, to give priority to one’s fellow citizens over those of other countries.” Schmittz points to economist (and Nobel laureate) Angus Deaton describing his ‘change of mind’ to illustrate how the consensus is now more skeptical of what used to be articles of faith — that open trade markets and an open approach to the border were good for the country, with the benefits generously outweighing the costs:

“I used to subscribe to the near consensus among economists that immigration to the U.S. was a good thing, with great benefits to the migrants and little or no cost to domestic low-skilled workers,” he wrote. “I no longer think so.” He added that he had also become “much more skeptical of the benefits of free trade to American workers” — and even of its role in reducing global poverty.

This ‘paradigm shift’ seems to be grounded in a recognition that because humans are rooted in their local environments, it is sensible for them to care more for those who are closer — even as we may want to expand our moral considerations and include people in other parts of the world. Like a parent cannot care as much about other people’s children as about their own — and in fact, that would be a betrayal of their parental task — they can care about other people’s children while prioritizing their own (i.e., these are not mutually exclusive). As Deaton put it:

I also no longer defend the idea that the harm done to working Americans by globalization was a reasonable price to pay for global poverty reduction because workers in America are so much better off than the global poor. … We certainly have a duty to aid those in distress, but we have additional obligations to our fellow citizens that we do not have to others.

Understood from this angle, the impulse to protect national sovereignty and identity is a potent and important expression of the traditional worldview that needs to be honored and build forth on, expanding it while respecting and integrating it.

Identity politics and the loss of the individual

While national identity was thus under pressure — and often seen as xenophobic — the postmodern worldview started emphasizing other forms of group identity, like race and sex. This was partially in reaction to Modernity’s individualism and its myth of ‘the self-made man’ — arguing that in many cases, no amount of individual responsibility could overcome the systemic and structural prejudices in society.

That is, modern, liberal approaches had sought to overcome group categories with the aim of treating people equally regardless of their identity (i.e., being ‘colorblind’) while emphasizing individual responsibility and self-determination. This was guided by the aspirational idea that people should not be determined by the groups they were born into (as had been the case in traditional societies), while underscoring the value and potential of each human. Commitment to meritocracy is a logical outcome of this.22

As Pluckrose and Lindsay argue, postmodern thinkers found this approach inadequate to address the deep-seated nature of racism, and discrimination more generally. Instead, these thinkers emphasized language, power, and dominant discourses, calling attention to discrimination’s systemic nature — involving legal and economic systems as well as invisible systems (e.g., of white supremacy and patriarchy), which through ‘unconscious bias’ and ‘societal narratives’ structurally disadvantage certain groups. With that, they shifted a largely materialist approach oriented to addressing economic discrepancies between groups to a largely idealist approach oriented to disrupting dominant discourses to create revolutionary change.

This recognition of discrimination’s embedded, unconscious, and often veiled nature is arguably an important advance. At the same time however, it risks making it all-pervasive and unverifiable, while fundamentally dividing societies into dominant versus marginalized identities (e.g., perpetrators versus victims, colonizers versus colonized), thereby potentially entrenching rather than overcoming the tendency to conceive of people as groups in balkanized opposition.

In the political realm, these ideas come to expression in D.E.I. initiatives, which became increasingly prominent on campuses and elsewhere in the last few decades (and are now being aborted because of Trump’s recent executive orders). Though importantly bringing awareness to structural identity-based bias, these programs may also devalue individuals and their qualifications (undermining meritocracy) while reifying stereotypes and entrenching group identities.23 In its more extreme forms, discrimination on the basis of whiteness (skin color) and/or maleness (sex) was justified, while making Black people into victims and discouraging their agency, resulting in what John McWhorter calls ‘woke racism’, in his book with the same title.

While Critical Race Theory and its expression in D.E.I. programs should have resulted in an expansion of the achievements of the Civil Rights Movement, the societal backlash that followed may be argued to underscore the limitations of the postmodern framework. In this worldview, both individual and universal tend to be rejected.24 As this worldview doesn’t recognize an intrinsic nature to reality — and in fact deems such ‘essentialism’ oppressive — it cannot validate a universal human nature. The resulting focus on identity-based groups, rather than our shared humanity, has arguably further divided society instead of being a healing force.

There’s also little evidence that these initiatives work. Studies show that mandatory trainings that blame dominant groups for D.E.I. problems may well have a net negative effect on the outcomes managers claim to care about. And although D.E.I has been controversial, instead of constructively engaging with the critique, the tendency has been to ‘blame the messenger’. In McWhorter’s words:

D.E.I. advocates may see their worldview and modus operandi as so wise and just that opposition can only come from racists and the otherwise morally compromised. But this is shortsighted. One can be very committed to the advancement of Black people while also seeing a certain ominous and prosecutorial groupthink in much of what has come to operate under the D.E.I. label. Not to mention an unwitting condescension to Black people.

While the postmodern worldview thus claims to promote inclusion, it’s become well-known for its exclusion of those who do not share its values (e.g., cancel culture). This is one of its contradictions: while it argues all perspectives to be equal, it clearly also believes that perspective to be superior. Related to this is its uneasy pairing of moral relativism with moral righteousness: while it erodes a sense of universal morality, it simultaneously claims the moral high ground.

Gender politics and the loss of sex

Another hot-button topic that arguably has had an outsize effect on the public’s rejection of the left, is its association with gender politics.25 However, as the right continues to radicalize its anti-trans position, it’s becoming (even) harder for the left to treat this issue with nuance and take a stand that might be in line with the right.26

Also, though some argue this issue not to be significant because it would only affect a small group, that idea underestimates how this debate — about what men and women are, and whether sex is real, consequential, and changeable — not only affects many domains of life but also touches on people’s foundational understanding of reality, thus rattling their worldviews.

Put simplistically, while the modern worldview tends to deny the existence of the inner (subjective) world, the postmodern worldview tends to deny the existence of the outer (objective) world. One way we’ve seen the latter come to expression is the idea that gender is merely a social construct — an identity based on one’s subjective self-sense rather than one’s objective biological sex. That is, gender is about what I feel my sexual identity to be, and this cannot be externally determined — it can only be self-declared, and thus not challenged or objectively checked.

Instead of understanding gender identity in addition to biological sex, transgender activists often frame it as overriding sex, which becomes clear in their demand for ‘gender self-identification’ — proposing to determine legal sex (as found in official documents like birth certificates and passports) on grounds of subjective gender-identity (instead of objective biological sex). Popularly this idea is expressed in the idea that ‘trans women are women’ — claiming there is no meaningful difference between biological males who’ve (socially and/or medically) transitioned to a female identity, and biologically born women.

The genuinely held belief in progressive circles is that agreement with this position is an issue of fundamental rights, and that any concession on this matter is ‘poor allyship’ and ‘throwing a marginalized group under the bus’. Though this appears as a principled position, the argument I advance here is that it’s not only empirically incorrect27 and strategically unwise (particularly given its electoral unpopularity28 and the anti-trans backlash it appears to evoke — which is obviously deeply harmful to transgender individuals), but also principally or morally flawed. That is, precisely if one opposes all forms of bigotry and discrimination, one must reckon with the fact that trans rights do not exist in isolation and cannot come at the expense of other (arguably also vulnerable) groups, whose rights similarly deserve protection.

Transgender activists often claim that gender identity is different from, and not determined by, sex. However, contradictory, they also argue that gender identity should grant one the rights associated with the sex one identifies with. Thus, while sex has nothing to do with gender, gender has everything to do with sex. Or to put that differently, rather than sex shaping gender, as humans had long understood it, gender replaces sex — with sex no longer having inherent meaning or consequences.

But sex cannot be replaced without violating reality and having far-reaching consequences in many domains of life, including health care, sports, speech, legal systems, data science, prisons, schools, and work places, to name but a few. That is, sex matters, as a recent article in the Guardian spells out:

Gender-questioning children and young people have been prescribed untested drugs with harmful side effects by NHS clinicians. Rape crisis services have failed to provide women who have been sexually assaulted with single-sex services. Male rapists and sex offenders who say they believe they are really women have been locked up in female prisons with vulnerable women. The police have unlawfully tried to discourage people who believe biological sex is real from exercising their democratic right to free speech. Employment tribunal rulings illustrate how many people – particularly women – who have refused to comply with this belief system have been bullied and hounded out of their workplaces. And now a new government-commissioned review led by Prof Alice Sullivan of University College London has highlighted the extent to which official data sources have been corrupted by gender ideology.

In other words, the negative real-world consequences of replacing sex with gender are all too real, particularly for, but not limited to, women ands girls.

Women’s rights are arguably sex-based and not identity-based. That is, these rights are to protect women on biological grounds — not because they identify as women, but because of their predicament in confrontation with a physically dominant other sex. By definition, if we give the so called ‘stronger sex’ the rights aimed to protect the ‘weaker sex’ from the ‘stronger sex’, those rights lose their purpose. That is, the whole point of women’s rights is that men don’t have them. Giving the other sex access to these rights thus directly undermines them. And these rights are no luxury, as statistics about violence and sexual assault against women unfortunately underscore.

However, there is another pathway. Instead of overriding sex with gender, sex may be complemented with gender. In that understanding, gender doesn’t erase sex: sex is recognized as having real-world consequences and as, generally speaking, manifesting in the male-female polarity (on which reproduction and thus the survival of our species is based). In addition, there may be alternative ways in which people identify, including as trans women and trans men, or as non-binary or queer. In this understanding, sex and gender co-exist, rather than one replacing the other.29

Changing culture through policing language

The left has also had a tendency to ‘police language’, grounded in the postmodern idea that language creates rather than reflects reality and is thus of critical importance when aspiring for social change. As part of such aspirations, common words have been problematized and politicized, sometimes with the intent to erase them altogether, including, notably, woman and mother.

Remarkably, progressive institutions — from academia to the medical profession to NGO’s — have largely submitted to this sex-denying policy and language. In many contexts, trans activist demands became the new norm, from needing to declare one’s gender in one’s email signature to the mainstreaming of factually problematic language like ‘sex assigned at birth’.30 These examples illustrate how constructivist ideas have captured the progressive intelligentsia31, arguably resulting in a cultural realignment where institutions once built around Enlightenment assumptions (rationalism, objectivism, universalism) were now, at least in part, guided by postmodern ones (constructivism, relativism, social activism).

At the same time, those who’ve challenged these ideas have been bullied, often viciously attacking their motives and character instead of substantively engaging with their — rather common sense — arguments, from J.K. Rowling to Helen Joyce to Kathleen Stock, to name but a few.32 However, the left-leaning media has generally failed to relay these women’s stories — portraying them as radical feminists and associating them with transphobia — largely adopting transgender activists’ framing that any resistance to their demands is a matter of intolerance or hatred.

This resulted in a censorial, Orwellian atmosphere in which simple truths could not be spoken and in which the ‘wrong’ use of innocent words quickly led to the conclusion that one is immoral. As evolutionary biologist Carola van Hooven explains:

… my troubles began when I described how biologists define male and female, and argued that these are invaluable terms that science educators in particular should not relinquish in response to pressure from ideologues. I emphasized that “understanding the facts about biology doesn’t prevent us from treating people with respect.” We can, I said, “respect their gender identities and use their preferred pronouns.” I also mentioned that educators are increasingly self-censoring, for fear that using the “wrong” language can result in being shunned or even fired.

Van Hooven left her position at Harvard because there was little institutional support for her speaking to biological facts. As she describes, though being a lifelong Democrat, her supporters have tended to come from the right. This is also what many others who spoke up against the ‘woke orthodoxy’ have found — including for example many de-transitioners, who for years were dismissed by progressive media as statistically irrelevant or right-wing talking points.33

Disturbingly, progressives have thus given away the important job of protecting women’s rights (and children’s rights) — so that a party that inexhaustibly worked to get rid of reproductive rights and is led by a convicted perpetrator, could claim credit for it. To this day, Democrats are fighting to keep biological males in women’s sports, even though this subverts the public’s opinion and is electorally a loser.34

Importantly, this position reveals the left’s up-side-down understanding of justice, aspiring for a world in which identifying as a woman will give you access to women’s rights, while being born into a woman’s body won’t, and in which the rights of a small minority are advanced by compromising the rights of half of the population. The left therefore shouldn’t be surprised that — especially as it became associated with insanities like replacing ‘mothers’ with ‘birthing people’ — the public lost trust it’s fighting for people like them, or even for something worthwhile.

The Woke Mind Virus: MAGA is not the only cult out there

While it’s obvious to progressives that MAGA is a cult more than an authentic political movement, we tend to be blind to our own cultish tendencies. Liberals love to watch political comedian Jordan Klepper question MAGA supporters, marvelling at their bigotry and internal inconsistency. However, watching conservative activist Matt Walsh question transgender activists may provoke a similar sensation — that these people are brainwashed, shutting down the interview when their inconsistencies are revealed, and happily sacrificing truth and rationality on the altar of ideology.

When Walsh asks these activists ‘what a woman is’, they often initially resist giving a definition, to then, when pressed, come to some variation of the answer that ‘a woman is anyone who says they’re a woman’. This, of course, is circular reasoning, and Walsh doesn’t take it for an answer. Noteworthily, his questioning reveals that those demanding to overturn the since time immemorial universally shared notion that there are consequential differences between men and women, are not willing to define what they mean, but will simply call the questioner a bigot or transphobe.

While progressives have declared themselves shocked at how easily conservatives seem to have given up on democracy,35 that shock is mutual, as conservatives have been stunned by how willing progressives have been to sacrifice the biological reality of sex, and thus the foundation of life. Though progressives often know better, the public pressure is enormous.36 So while one side is unable to unequivocally state who won the 2020 presidential election, the other side is unable to state what a woman is (including Supreme Court justices) — and it’s perhaps not surprising that the public may find the latter (even) more disconcerting than the former.

It thus appears that both MAGA Cult and Woke Mind Virus are not just figments of the imagination or projections of the other side. Radicalized by the polarization-dynamics of the last few decades, both sides have become increasingly impenetrable to reason. Instead of critically scrutinizing the different arguments in any issue, and on that ground crafting a viable political vision, the tendency has been to reflexively double down on the position diametrically opposed to what the other side thinks. With that, the rational middle ground disappears. As each side moves in opposite directions, becoming more extreme in their positions, the shared middle — the modern belief in science, rationality, and global capitalism — has eroded.

While conservative political parties used to represent both the traditional ‘religious right’ (social conservatives) and more modern sensibilities (fiscal conservatives), in the last few decades they’ve moved towards a more singularly populist-traditional worldview — displaying an increasingly isolationist, anti-establishment attitude. This is manifest in, amongst others, hostility toward free trade and globalism, NATO and multilateral institutions, and big corporations and science.

Similarly, while progressive parties used to represent both modern and postmodern impulses in society, they’ve become increasingly subservient to a postmodern ideology that rejects liberal, modern principles, from a commitment to science and free speech to the embrace of viewpoint diversity and democratic debate.

That is, the dynamics of polarization and radicalization have gradually devolved both sides into intolerant ideologies rather than inclusive worldviews, with the modern worldview — once functioning as the common ground between traditionalism and postmodernism — now under attack from both sides. Though arguably both sides cannot be equated, with the right displaying considerably more extreme attitudes and behaviors37, qualitatively the similarities in authoritarian tendencies are striking, as commentators have noted. And while both sides have recognized these illiberal tendencies in the other, they tend to deny it on their own side.

The hall of mirrors: Splitting, projection, and reversals

A remarkable characteristic of our political landscape is the amount of mirroring taking place — with parties accusing each other of what they’re doing themselves, with splitting, and position-reversals — up to the point that it appears like a trippy Alex Grey painting (though it isn’t as pretty, to make an understatement).

The psychological concept of projection powerfully illumines this. Projection is a psychological defense mechanism that results in humans accusing others of what they do themselves. That is, they mistake ‘inside’ content to come from ‘outside’ other. Freud believed that thoughts, feelings, and behaviors unacceptable to the ego were defended against by disowning and projecting them — denying their existence in oneself and attributing them to others. What the ego refuses to accept is ‘split off’ and placed outside. Jung referred to these disowned parts of self as ‘the shadow’ — the parts of us that stay in the dark and don’t reach the light of consciousness.

Clinical psychologist and couples therapist Orna Guralnik sees this splitting mechanism in both intimate and political relating:

… splitting allows us to avoid dealing with feelings of vulnerability, shame, hate, ambivalence or anxiety by externalizing (or dumping) unwanted emotions onto others. We then feel free to categorize these others as entirely negative, while seeing ourselves as good. … In political environments, this kind of splitting manifests in an “us versus them” mentality — where “our” side is virtuous and correct, and “their” side is wrong and flawed — which produces the kind of rigid, extreme, ideological warring we are caught up in now.

She also emphasizes how important it is for us to recognize how gratifying this process can be, both for individuals and larger groups:

Splitting produces a kind of ecstatic righteousness. There’s an intoxicating thrill in hate — in feeling that you’re in the bosom of a like-minded brotherhood, free from complexity and uncertainty. In this state, we’re prone to ignore information that contradicts our idealized version of ourselves, we become allergic to dissonance, and those with differing views are cast out or canceled.

An obvious example of projection is Trump’s “stop the steal” mantra, which he kept repeating while he himself attempted to steal the election (culminating in his attempt to obstruct the legitimate transfer of power on January 6th ‘21). Projection also explains why he could lie so shamelessly and with such persuasion: he accurately sensed the election was attempted to being stolen, while confusing inside with outside. In Jungian terms, his attempts to steal were unconscious shadow — seen but without full recognition that it was himself standing in the way of the light.

Arguably, Trump also used this mechanism strategically as he wouldn’t have gotten away with his brazen attempts to overturn the election, be it for him consistently ‘throwing sand in people’s eyes’ by claiming it was the other side doing the steal. One may therefore also see it as informational warfare, which is particularly effective in highly polarized environments, where not being able to see dovetails with not wanting to see. However, while the MAGA-right appears to have a particular penchant to project their violations unto the left, many of their claims also hold a grain of truth — aligning with Freud’s understanding that projection tends to seize on, and exaggerate, an element that does exist, albeit subtly, in the other person.

This is also where the discernment of truth becomes nearly impossible, even for a well-intentioned public. That is, Trump not only succeeds in projecting his violations on his adversaries because he is a masterful con artist, but also because there has been a good target to project onto — with a political left that has shown itself to be, at least at times, out of touch, authoritarian, and disrespectful of the public’s views. The left also displayed ‘Trump Derangement Syndrome’ — rejecting anything Trump says or does, regardless of its merits. (The right, in its near-religious devotion to Trump, of course shows the exact flip side to this: it bows to the king.)

Whether driven by blind hatred or blind loyalty, both sides have over time redefined themselves, often in ideological reversals that contradict their historical beliefs. As nuance and the middle ground disappear and politics increasingly become a zero-sum game, polarization-dynamics result in the reduction of innumerable options into only two acceptable positions, creating a political binary trap. In such an environment, evolution in ideas happens by flipping from one extreme to the other.

Reversals: Left became right, and right became left

While conservatives used to represent the establishment, and progressives used to be the party of the working people, over the past few decades a profound reversal has taken place, with conservatives and progressives trading attitudes and impulses across a range of issues. As Ross Douthat argued:

The populist right’s attitude toward American institutions has the flavor of the 1970s — skeptical, pessimistic, paranoid — while the mainstream, MSNBC-watching left has a strange new respect for the F.B.I. and C.I.A. The online right likes transgression for its own sake, while cultural progressivism dabbles in censorship and worries that the First Amendment goes too far. Trumpian conservatism flirts with postmodernism and channels Michel Foucault; its progressive rivals are institutionalist, moralistic, confident in official narratives and establishment credentials.

Paradoxically, as progressives gained in cultural and economic power, not in the least through their growing influence on a wide swath of institutions in society, the left that had been intensely establishment-critical now became the establishment. Many of its ideas became policy, as for example the size of the D.E.I. industry illustrates.38 Yet, postmoderns still tended to see themselves as the underdog fighting ‘the system.’ Simultaneously, while conservatives used to defend the establishment, they came to see themselves as battling an entrenched, authoritarian, progressive elite.39

These dynamics thus resulted in the parties switching positions, with the right becoming the anti-establishment party.40 The pandemic seems to have exacerbated this process, as leftist political parties defended the status quo that conservatives attacked. (One may also argue however that the left’s pandemic response has been largely consistent with its central commitment to protecting the public good — i.e., public health — while underscoring the role of government in that aim.)

In any case, as the cultural left had become more powerful and the cultural right more marginal, the left had less patience for contrarian positions, which the right in its new context found particularly useful. Representing the establishment, the left required “piety and loyalty more than accusation and critique”, as Dhoutat argued:

This is most apparent with the debates over Covid-19. You could imagine a timeline in which the left was much more skeptical of experts, lockdowns and vaccine requirements — deploying Foucauldian categories to champion the individual’s bodily autonomy against the state’s system of control, defending popular skepticism against official knowledge, rejecting bureaucratic health management as just another mask for centralizing power.

But left-wingers with those impulses have ended up allied with the populist and conspiratorial right. Meanwhile, the left writ large opted instead for a striking merger of technocracy and progressive ideology: a world of “Believe the science,” where science required pandemic lockdowns but made exceptions for a March for Black Trans Lives, where Covid and structural racism were both public health emergencies, where scientific legitimacy and identity politics weren’t opposed but intertwined.

The ‘crunchy’ (i.e., ecology-and-natural-health-oriented) part of the postmodern electorate was particularly sensitive to anti-vaccine, anti-state-control, and pro-bodily-autonomy positions. When progressive parties defended mainstream pandemic responses, a substantial number of them — particularly those adhering to strong anti-establishment or conspiracy-like views — were driven to the right. The postmodern worldview, though generally understood as a leftist phenomenon, may thus also fuel the right, particularly the MAHA right.41

For example, RFK, a former pro-choice Democrat and progressive environmentalist, these days finds his anti-establishment positions — i.e, his skepticism of Big Food, Pharma, and Agriculture — easier to align with the (MAHA) right than the left. Also Musk and others of the ‘tech broligarchy’ used to be associated with progressive politics. Similarly, conservatives unable to square their values with the new Trumpian right, found themselves, sometimes begrudgingly, in the leftist ‘camp’. Some therefore argue that the left-right binary lost its meaning, with the dividing line now being populist vs establishment or autocracy vs democracy.42

Anomalies demanding a paradigm-shift

The 2024 election year may be seen as the ‘nail in the coffin’ of the postmodern worldview dominating cultural and institutional narratives, particularly in its more extremist, ideological expressions.

Remarkably, while running on an anti-immigration platform and promising mass deportations, Trump increased his support among Black, Latino, and Asian voters, from 2016 to 2020, and then again from 2020 to 2024. As Ezra Klein noted:

That was, to put it very mildly, not what Democrats expected. Trump was the xenophobe in chief. Democrats were appalled by the way he talked about immigrants, about Muslims, about China, about Black communities. The theory was that Trump was using racism and nationalism to drive up his margins among white voters.

While Trump, with that approach, was expected to alienate non-white voters, he instead managed to build an impressive, multiracial coalition, coalescing around a working-class identity. This presents us with an anomaly that challenges the assumptions of the postmodern paradigm, as David Brooks argued:

This identity politics mind-set is psychologically and morally compelling. In an individualistic age, it gives people a sense of membership in a group. It helps them organize their lives around a noble cause, fighting oppression. But this mind-set has just crashed against the rocks of reality. This model assumes that people are primarily motivated by identity group solidarity. [it] assumes that the struggle against oppressive systems and groups is the central subject of politics.

The modern dream of material prosperity through a global, technologically advanced, capitalist society had been failing for a long time. Its postmodern alternative —continuing the modernist pathway into the neoliberal era while offering a sense of moral righteousness through identity-based activism — has now also been rejected. And understandably so, as both its tactics and policy proposals did not embody the inclusion it preached, while failing to create the inclusive society it promised.

This means we should reconsider our assumptions and, as Brooks put it, start the “gigantic cultural task” of forging a new worldview.

A recipe for renewal: Cultural moderation + economic populism

The task of this new worldview is considerable: it must help people make sense of our complex world while offering constructive guidance for action and direction in their lives. To be successful in our current Zeitgeist — and, not unimportantly, avoid instigating more cultural backlashes — it must integrate the greatest qualities and achievements of the multiple worldviews present in society. This also means the left has to reckon with how ideological it has become and craft a more truly inclusive vision, seeking to synergize — rather than polarize — with other worldviews while developing pragmatic solutions to people’s real-world challenges.

We thus must come to a relentlessly pragmatic, non-ideological approach that combines compassionate humanity with solid rationality. Concretely, we must find ways to protect immigrants and refugees while honouring that countries need secure borders. We must find ways to protect minority-groups while respecting the agency of the individual. And we must find ways to protect transgender people while respecting women’s rights and children’s safety. Thankfully, constructive suggestions for how to achieve our noble diversity and inclusion aims without falling in the trap of extremism are already being put forward. (For example, the Institute for Cultural Evolution develops policy recommendations on diverse issues, attempting to honor the central values and concerns of traditional, modern, and postmodern worldviews. )43

Re-envisioning our worldview is a demanding task, most of all psychologically. It demands us to admit our mistakes and jump over our shadows. It demands us to question our assumptions. Rather than fuelling the culture wars, we must meet the right halfway — not buying into its extremism but integrating the enduring values and qualities it speaks to.44 That is, given the election-outcome, arguably also what the public asks from us. However, this is not a simple “both-sides-ism.” In my opinion, the left is substantially better — but being better puts the responsibility on us to also be wiser. And wisdom is to start ‘manoeuvring’ us out of the culture wars, which are doing untold damage to our planet and all its creatures.

A recipe for a revitalized leftists politics therefore needs to combine cultural moderation with economic populism — thus responding to both the cultural backlash and the economic insecurity at the heart of the right-wing populist revolt in the West.

This recipe also respects the left’s core value of inclusion. That is, including diverse perspectives in society will necessarily result in more culturally moderate positions, while including people economically implies economic populism. Politicians like Bernie Sanders and A.O.C — these days in the spotlight with their ‘fighting oligarchy’ rallies that draw massive crowds — may fit this profile, as they’re solidly on the left on the economics, while being pragmatic and connected-enough to the interests of real people to understand that extremist cultural views don’t serve the public good.

Contours of a newly emerging worldview

It’s arguably only when polarization reaches its maximum, that a new integration can come about. Perhaps we’ve now reached that point. In response to the toxic polarization45 of our time, the new worldview attempts to integrate and unify, heal and make whole again. It emphasizes nuance and complexity. It recognizes interconnectedness and mutuality. It plays with synthesis and paradox.

It cannot stand in either of the extreme poles now dominating our current political landscape but must hold — and move beyond — both. Psychologically, this may be supported by what Jung referred to as individuation, speaking to the process of becoming a fully developed, unique individual by integrating the various polarities of one’s own psyche — like rational vs emotional, masculine vs feminine, and conscious vs unconscious — into a harmonious, cohesive whole.

This worldview also has to restore the enchantment, communality, and connection to the sacred that is ubiquitous in pre-modern and indigenous worldviews, yet is severed in the process of modernization — resulting in the pervasive sense of alienation and meaninglessness that characterize both modern and postmodern worldviews. As research underscores, a sense of meaning, inner purpose, and community are crucial for human well-being and cannot be replaced by high levels of economic prosperity.

This new worldview therefore starts from the recognition that earlier worldviews have important insights to offer, as each of them embodies the solutions to the problems of their time, as well as diverse insights, qualities, and values. It aims to reveal that what seem like mutually exclusive opposites may in fact be expressions of a deeper unity. As we’ve seen in the above analysis, the left and right — with their mirroring, projections, and reversals — are more interconnected and alike than they appear on the surface. Think of Niels Bohr’s axiom in quantum physics: “The opposite of a profound truth may very well be another profound truth.” Or of the Taoist yin-yang symbol, depicting an opposite yet interconnected, self-perpetuating cycle and whole, with each side of the polarity carrying the other as its essence.

Jean Gebser, a prescient philosopher of the new worldview, spoke to the totalizing tendencies of worldviews — believing their perspectives reflect the totality of reality rather than a partial perspective on it. As Ken Wilber pithily put it, most human perspectives are “true but partial”. Or as John Stuart Mill once said, referring to the different sides in intellectual controversies, they tend to be “in the right in what they affirmed, though in the wrong in what they denied.”46

Following Mill, one may recognize that the traditional worldview is right in its affirmation of a transcendental divine, a sense of higher purpose, and the importance of social solidarity and national sovereignty, while being wrong in its denial of the this-worldly and its repression of the individual. The modern worldview is right in its affirmation of material, physical reality, the human powers of reason and logic, and its commitment to democracy and free speech, while it’s wrong in its denial of the non-material and non-measurable as well as its disavowal of the subjective and inner realms. Similarly, the postmodern worldview is right in its keen recognition of how humans construct their world, its noble desire to include, and its sensitivity to marginalized groups, while it’s wrong in its dismissal of the objective world, the agency of the individual, and more universal values and realities.

Rather than discarding the past, this new worldview thus has to act as a meta-framework — forging a synthesis that integrates and yet transcends previous ways of seeing the world. This is a both/and, not an either/or shift. It doesn’t deny nor side with any of the polarities, but sees them as expressions of a deeper unity. That is, it attempts to integrate into a greater whole both object and subject, both science and spirituality, both nature and humanity, both male and female. Though this admittedly is a stupendous task, a score of philosophers and thinkers, change-makers and visionaries, has already been working on it for at least a century.

This new worldview thus builds forth on the postmodern call for inclusion, yet takes it further, ultimately integrating its political opposite. Some have therefore referred to it as an integral or integrative worldview, an evolutionary worldview, a meta-modern worldview, or a complexity paradigm. When I asked Chat-GTP to describe the “change of worldview we need to respond to the existential crisis we’re in”, it spit out a list of features, including a shift from separation to interconnectedness, from anthropocentrism to earth-centered awareness, from extractive growth to regenerative economics, from individualism to more relational forms of being, from short-term to long-term thinking, and from fear and control to trust and emergence.

This new worldview must also appreciate that we’re living through an existential, planetary crisis, with crises manifesting in nearly every facet of our existence — from education, (mental) health, and culture, to democracy, environment, and institutions — unsettling societies around the globe. Simultaneously, we need to interpret this crisis in an empowering way. That is, we need a visionary story that recognizes the many crises as fundamentally interconnected, with humans having a rewarding, creative role to play in addressing them.

This is perhaps why notions of poly-crisis47 and meta-crisis have gained traction in the past years. In this perspective, humanity’s myriad crises are like the many heads of a monster, pointing to a deeper crisis — a crisis in how we understand ourselves in the universe, and therefore of how we give meaning, and thus shape, to our world. This crisis is often envisioned as inviting for a collective initiation, catalyzing a painful but necessary transformation process that may mature humanity into a wiser species. This is a lofty vision that may help us unleash our vast human potential, with each of us invited, in our own unique ways, to creatively contribute to the daunting issues we face, birthing a new world of beauty and love, nature and peace.

Acknowledgements: I want to thank for their helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this article: Hülya Kosar-Altinyelken, Richard Tarnas, Maartje Peters, Pieter Stokkink, Matthew David Segall, Linda Urban, Peter Blom, Maarten Robben, Rebecca Bouhuijs, and Peter Schmitt.

Though the right-left binary is, of course, questionable — with its ever-changing meanings and position-reversals — it does accurately display the left and right as opposites, where what one is cannot be understood independently from what the other is. I’m using the terms left and right here to broadly orient us in our political landscape, with the left generally referring to the parties that believe in the need to protect the common good and prescribe a significant role for governments, while the right emphasizes the need to protect individual freedoms and prescribes restraint of government.

As Fareed Zakaria put it, “almost everywhere you look, the left is in ruins.”

My focus here is on the Western world, and the USA in particular.

Later sociological work in the form of the World Values Survey has demonstrated that people’s values and beliefs indeed play a key role in economic development, while economic development simultaneously is foundational for cultural value change, thus asserting the mutual interaction, and relevance of both economics and culture.